Quickly, the yard was full with books lying on top of each other. When the library was emptied, one of the men took out a match and put the books on fire. One of the other men closed the gate to the yard as the other men gripped and pulled the women’s frightened children from their arms and threw them into the fire. The mothers instinctively rushed to save their children, as the men opened fire and shot the women who fell into the flames. The men didn’t stop piling up the women in the big fire until all women were dead. In the yard, there were now only ashes left. A ten-year-old girl survived the massacre; she became an eyewitness.

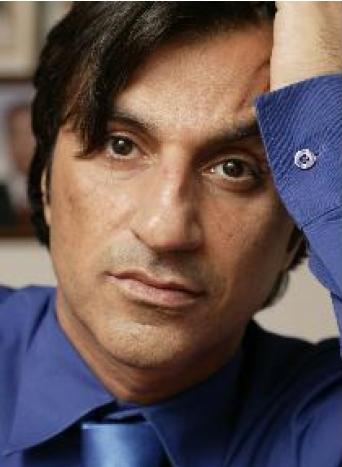

This is one of the many stories of the genocide that has now – about 90 years later- brought me to an apartment in Jakobsberg, a densely populated suburb in northern Stockholm. We are sitting in a small living room with the blinds down in order to keep out the strong rays of the sun. We talk about our background. Three of the men in the room have been in jail; imprisoned from 11 to 15 years. A forth man says that he was too smart for the Turkish state. I, myself, was too young to be one of the politically active students in the beginning of the 70s and the 80s in Turkey. Compared to the others, I am Assyrian, but we are all born in Turkey. We are all interested in our motherland and its development, and we are all writers. They write for a web paper called Nasname. A website for intellectual Kurds in the diaspora. Even if the sun is gushing through the blinds making the room stuffy, the room is still filled with activity. The men are going to publish several artic les about a seminar that was held in the Swedish parliament a few hours ago. One of the men, Behzat Bilek, was one of the main characters at the seminar who up until noon today was known as Berzan Boti. His real identity had been kept disclosed because of his fear of reprisals for his action; an action he has dreamt of doing.

He is the grandchild of one of the Kurdish perpetrators from Siirt. And he wants to be the first to apologize for the genocide committed on Assyrians, Armenians and Greeks in Turkey during the First World War. He doesn’t only want to apologize with words; he wants to apologize with an action. Behzad has given the title deed to the property he inherited from his grandfather who had confiscated it from Assyrians after they were murdered in the genocide. Behzad has given back his share of the family’s land. In 1991, after he had spent 12 years in prison due to, as he himself puts it, fighting for human rights and justice he decided to redeem his grandfather’s deeds. “I couldn’t live with myself as fighter for freedom knowing that my inherited property was stolen; knowing that blood had been shed in order for me to inherit this land”.

Behzad says that he didn’t know about the genocide until he, as an adult, started researching it. It was never taught in school, and at home it was also tabooed to mention. Today, Behzat is living in the city of Mersin. Most of his nine siblings have also left Siirt, but their mother still lives there. “It wasn’t until I had spoken to my mother that I finally made up my mind. She gave me her support and she said that what I was about to do was honorable”.

I don’t quite understand how things will be settled in practice. Behzad has nine siblings which all are heir to the property he now has given away.

Seyfo Center is a lobby-organization in Holland with members and offices all over the western world. Seyfo is the Assyrian word for sword and the name Assyrians use in reference to the genocide during the First World War.

Sabri Atman is a Swedish citizen; this is why the official hand over of the title deeds of the property was held in the Swedish parliament. Another reason for Seyfo Center to choose the Swedish parliament as the place where the title deed would be handled over was due to the fact that many Swedish members of the parliament have been involved in getting Turkey to recognize the genocide. It was a very emotional ceremony. Many of the people present couldn’t hold back the tears, including Behzad himself.

Back in the living room in Jakobsberg, one of the men is pouring up tea for us while Behzat looks in to my eyes and continues his reasoning.” Finally, I can relax and let go. From the time I made my decision till the time it was done, it has been very difficult for me. My wife, who is an attorney, has supported me the most. Our biggest concern is our ten-year-old daughter, who tells me that she doesn’t want to live without a father. Up until now, I have only received positive reactions, but I also know that my actions have made me some enemies as well.”

Now he is less tense and says that I may ask any questions I would like to ask. He has nothing to hide, he says. I question what he has done. I don’t understand how it is going to happen in practice and what will happen if Sabri Atman decides to sell the land. I even question the property’s worth.” We are talking about 5 000 hectare that will be divided among ten people, my nine siblings and Sabri Atman who will get my share. How and when, I don’t know. The future will tell. All I know is that I feel happy. I feel that I have created history, and I hope that my action will contribute to recognition. This is now more than just a symbolic action.”

I begin to irritate the other men with my constant questioning. Behzat has done something great. After all, it is the symbolic value that counts. Most Kurds, and Turks for that matter, don’t even know about the genocide. Now it has been confirmed by the grandchild to one of the perpetrator’s. I give up. None of the four Kurds in Jakobsberg knows any details about the genocide; they don’t even know about the massacre in the city of Siirt where Behzad was born.

The day after, I call the research assistant, Jan Beth Sawoce. He is the one who told me the story about the ten-year-old girl who survived the massacre in Siirt. “One of the most well known intellectual orientalists lived in Siirt at that time. So did the Chaldean-catholic archbishop, Mon Signor Aday Sher, who was in charge of the Mor Jakup cathedral. Throughout his years in Siirt, he was mostly known for his book collection and for the cathedral’s library with its 30 000 books. Mon Signor Aday Sher was an author himself of books with theological, philosophical and linguistic theme.”

It was exactly those books that were used in the fire when the four Kurdish men murdered the widows and their children. The cathedral was a culture center and its books were invaluable to Assyrians (who also go under the denominations of “Chaldeans” and “Syrians“). This is the reason why Beth Sawoce has decided to focus on this city. Beth Sawoce works at the University of Södertörn in southern Stockholm. Together with Professor David Gaunt, he writes on his second book about the genocide of non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

When I meet Sabri Atman he looks relieved, just like Behzat. It has been trying times. He has feared that the hand over of the title deeds would be sabotaged. “Of course it is not about the land itself; it is the action. You were there and saw how many cried when we shook hands yesterday. It is historical; it is a beginning to recognition, but it is also a beginning to reconciliation. Until the last minute before going public about his real identity, Behzat had to keep it a secret because we feared that he would be hurt or that someone would somehow sabotage everything. Now we will see what will happen next. None of us knows how things will develop or what this can lead to. One thing is sure though, Assyrians worldwide have gotten a very eagerly awaited recognition. Behzat’s action is heroic and honorable. It is just a shame that the little girl who survived the massacre in Siirt isn’t alive to experience this historical moment.”

See pictures from the press-conference in the Swedish Parliament.

By: Nuri Kino

© Bethnahrin.de

Alle Rechte vorbehalten

Vervielfältigung nur mit unserer ausdrücklichen Genehmigung!