Please tell us about your personal background.

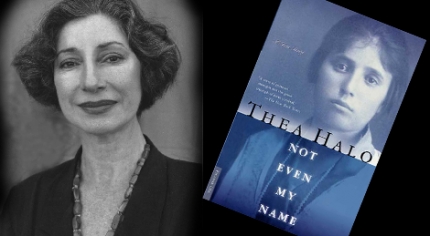

From an early age I wanted to be an artist. I attended the Cooper Union School of Art and Architecture rather late in life, and then I attended State University New York, where I was given a Fellowship. But I’ve also worked as a columnist for a newspaper, a news correspondent for public radio and I’ve produced a number of programs for radio. In 1992 I began to write my mother’s story after taking her to Turkey to find her home 70 years after her exile. I have always been interested in exploring all my capabilities, especially those related to the arts.

Since the 2007 recognition of the Assyrian and Greek genocides by the International Association of Genocide Scholars, a landmark event in which you played a leading role, do you consider awareness of the Assyrian and Greek genocides to have increased amongst the academic community?

I do believe it’s increased. There are now a number of books that have been written about the Greeks and about the Assyrians. At least one major book about the Greek Genocide is a direct result of that resolution. I think more interest will develop as time goes on for both groups, but one must stay vigilant to make real progress.

You have written of the culpability of some victim groups in the denial of the experiences of others. Indeed, you have suggested that ‘the expropriation by a single group of such monumental evil’ serves to ensure the fulfilment of their genocide. Other writers, including noted genocide scholar, Prof. Israel Charney, have recently written in a similar vein. Do you believe that the denial you have discussed continues today?

At my first IAGS conference, I found no one speaking about the Greeks or Assyrians. One important Armenian scholar actually denied the reality of the Greek Genocide during Q&A of my panel. His denial sparked my activism. I think the denial does still exist with certain people. For some it’s difficult to let go of the desire or need to feel exclusive in one’s suffering. There is also a danger that this need for exclusivity has other, more onerous, monetary motives. But I also believe that more scholars are willing to look at the larger picture to understand what took place, especially after the IAGS Resolution. This should be encouraged.

As you are aware, scholars focusing on the Assyrian Genocide are few. Why do genocide scholars broadly speak so little about the fate of co-victims of the Ottoman Empire’s genocide (the Assyrians and Greeks), as opposed to that of the Armenians? Are Assyrians themselves to blame for this reality?

I think the easy answer is that when a particular ethnic group spends so much time and resources to do extensive research and write books, and/or gives grants to others to write about their genocide, it would take a very generous spirit to focus on other genocides while trying to uncover the myriad facts surrounding one’s own history. It seems to be a prevailing view that the Armenians have done so much work and now that they’ve made progress, the Greeks and Assyrians want to have the benefit from their hard work. In a superficial way, it’s difficult not to sympathize with that view.

My main objection is, not that the Armenians should have done the work for the Greeks and Assyrians, but that they should have at the very least verified that the Greeks and Assyrians also suffered a genocide at the same time and place. That for me was, and is the only real obligation, so that others might be aware that more work needs to be done, which would hopefully encouraged other scholars to put in the time and effort to uncover the facts. Since so many of the documents mention both Greeks and Armenians, or Assyrians and Armenians, it would have taken no effort for a scholar to include mention of those documents to allow the public to know that there is a larger picture that needs to be explored. This holds true for the Holocaust’s other victims as well. The Assyrians should be vigilant in pointing out the discrepancies in texts when they find them to keep scholars and publishers honest. But no. The Assyrians are not to blame for the actions of others. Of course, Assyrians can always do more to protect their own interests, while also acknowledging the larger picture.

Do you consider Assyrians to have done too little to date in the pursuit of recognition and justice?

It would be easy to simply say; Yes. The Assyrians bear the responsibility. But unless I know under what circumstances the Assyrians have been struggling to gain a voice, or other circumstances in the Assyrian community, I can’t assume that it was something they could have accomplished easily. There were and are Assyrian scholars who wrote about the genocide. But unfortunately, it’s mainly the personal stories that find their way into the mainstream, and it’s not always easy to write such books. Nor is it easy to get them published by a mainstream publisher that could help the story reach the larger public. History books have a very limited audience, unless the subject matter is already one that is sought after. So, Assyrians can do more now that the door is open, and should do more… and some are doing more and have made great progress. We shouldn’t forget that. But to blame Assyrians for the past is not productive. Remember, it took me most of my life to know that I am an Assyrian, and if I had not had the talent or drive to tell my mother’s story, and if I hadn’t taken her to Turkey to find her home, my book would not have been written either. Now that the awareness is more pronounced, and we see the possibilities of what can be accomplished, now there is less excuse to turn away. But not everyone is cut out to make the grand gesture. What we should all keep in mind is the fact that each can help in his or her way, no matter how small. Even the small efforts add up to a big gift to the community.

Is the pursuit of political recognition of the genocide by Assyrian groups a squandering of minimal resources? Should the focus be on greater academic output and awareness?

Everything one does has a place in bringing the subject to the public. Each must do what his or her talents allow. One can’t force oneself to become a great author for instance. But one may be able to help a scholar do some of the research, or offer to translate primary documents. Or funds can be raised to support a good author to tell a good story properly. One can record survivor stories to make sure they are preserved, although today few survivors are still alive. But one can also record the stories remembered by the children of survivors. Some people might have organizational skills. Or they can write essays and attend conferences to lend their voice to the discussion. One need not rule out one avenue to pursue another. All avenues eventually lead to success. There are many ways to help the cause.

How best can diaspora Assyrians ensure that their genocide narrative is not forgotten? What advice would you give to young Assyrians?

We can learn from the Armenians. They have been very dedicated and methodical in their approach to this subject. They are a great model for the Assyrian community to emulate. Be creative in your approach. Think outside the box, as they say. One can study this subject to know it more thoroughly and learn how to write proper scholarly essays and even books. I attended my first genocide conference in 2003. Except for the 2007 conference, at which the vote for the resolution was to be made, I was the only Greek or Assyrian who attended those conferences to give papers on the Greek and Assyrian Genocides. Yet, at every conference, there were numerous Armenians or those who write about the Armenians giving papers on the Armenian Genocide.

What can Assyrians and Greeks learn from the activism of our Armenian brothers and sisters?

It takes dedication to excel. That’s what the Armenians who have made such contributions have… dedication to this cause. It would help to follow in their footsteps. Learn from them. I’m told that there are Armenians who give millions to sponsor one of the most important Armenian foundations, which in turn sponsors chairs at universities, gives grants to scholars to write books about the Armenian Genocide, etc. There is not one way to proceed. Each must do what he or she is capable of doing. I remember at one Peter Balakian event, an effort was made to encourage people to buy 10 of his books to give to non-Armenians as gifts. Now that’s a simple thing one can do to spread the word that takes no personal talent, but can be a valuable contribution all the same.

What plans to you have for future activism on the genocide issue?

I have been working on a history book of the Ottoman Empire that will include the Genocide of the Greeks, Assyrians and Armenians. I am writing it to dispel some of the myths that a few of the scholars used to fight against the IAGS resolution. And I still occasionally give papers at conferences. Of course, my dream is to have my book, Not Even My Name, made into a feature film. I believe that’s the kind of project that will really get the world’s attention if it is done properly.

© Bethnahrin.de

Alle Rechte vorbehalten

Vervielfältigung nur mit unserer ausdrücklichen Genehmigung!